The historical period I know most about is the ancient world, so the Battle of Agincourt is rather over two thousand years in my characters' future. Nevertheless, there are some interesting parallels. The main thing I knew about Agincourt - other than that it took place 600 years ago in 1415 - was that longbows had won the day. Sure enough, a poster I saw on the London Underground last week confirmed this by showing a rather dogged, defiant man, bow at full stretch, to symbolise the whole battle.

|

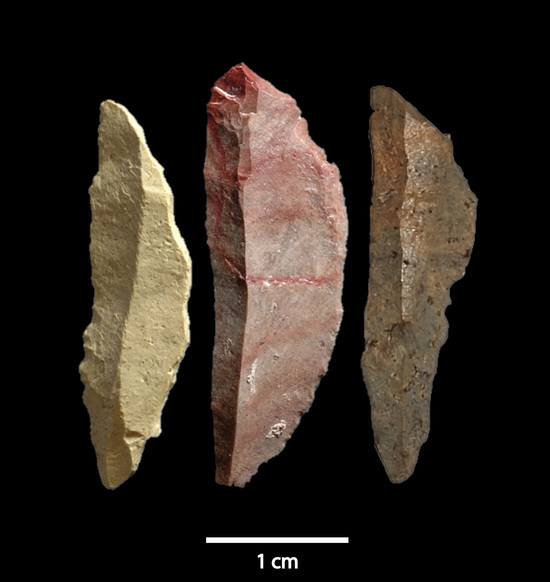

| Smithsonian image - possible early arrow heads |

The bow is at least 10,000 years old - some evidence suggests over 70,000 - and through all that time has served as both hunting tool and weapon of war. Early arrow heads are found quite often, but bows are less long lived, and the earliest European bow discovered so far dates from around 6000BC. The technological challenge in all that time has been how to gain more power. More power equals more range, or more destructive effect at the same range. But the basic design has remained the same.

Now, bowmakers have achieved more power either by careful choice of wood, skilled use of the grain, physical size, or careful splicing of the wood with other materials such as horn to give a composite bow. All of the above have to be combined with training, so that the user develops the physical strength and steady aim to make effective use of the weapon. Back in Medieval times, such training was compulsory, and the many streets called The Butts up and down the country recall that training.

In the Late Bronze Age, a typical composite bow might have a range of over 300 metres, with effective range against protected troops of about half that. Many cultures, from Egypt across to North India, used lightly built chariots as missile platforms, manoeuvring rapidly ahead of enemy formations to disorganise and weaken them. Other groups, chiefly those living on the steppe or the plains, used mounted archers for a similar purpose. Oddly, the Romans seemed not to rate bows highly, preferring to recruit auxiliaries for this purpose, but every other ancient culture I know of regarded them highly - numerous deities were closely linked to archery, so the skill had divine sanction.

|

| Wikipedia image, English longbow 6'6" in length |

Back at Agincourt and other battles of the age, a longbow in the hands of a skilled man had a maximum range of up to 400m, and was reputed to penetrate armour at half that. Moreover, the firing rate was immense - it is said that at Crecy, 6000 archers launched 42,000 arrows per minute. Against a slow moving or closely packed group of enemies, the effect was murderous. Keeping up such a rapid rate of fire was exhausting, however, and should be likened to a sprint rather than a distance run.

The interesting parallel to the Late Bronze Age is that in both cases, changes in military technology are linked to social transformation. In both cases, the dominance of a settled elite group - the mounted knight or the charioteer - was broken by the innovative use of simple weapons. Noble birth and heritage was no guarantee of survival, and a process of social levelling took place.

So what led to the decline of the bow? Quite simply, the gun. Early guns were certainly inaccurate and risky to use, but they had a longer range than a bow, needed no particular strength to use as weapon, and could be put in the hands of comparatively unskilled soldiers. By around 1600, bows had essentially disappeared from the battlefield except for isolated unusual cases.

They emerged again, and have survived until now, as a sporting piece. Regency and early Victorian writings tell us that archery was considered an entirely suitable sport for a woman, and archery clubs had members of both sexes. A far cry from the battlefields of the Hundred Years' War perhaps, but probably a whole lot more fun as well!

| From Agincourt600 web site |

Richard Abbott lives in London, England. He writes about the ancient Middle East - Egypt, Canaan and Israel - and when not writing words or computer code, he enjoys spending time with family, walking, and wildlife, ideally combining all three pursuits in the English Lake District. He is the author of In a Milk and Honeyed Land, Scenes From a Life and The Flame Before Us. He can be found at his website or blog, on Google+, Goodreads, Facebook and Twitter.

I'm really interested in weaponry, and this is post is a keeper, Richard.

ReplyDeleteI'm really interested in weaponry, and this is post is a keeper, Richard.

ReplyDeleteNot just the Romans, the Greek city states too. Strange that the Classical world preferred using javelins over bows, I wonder why?

ReplyDelete