After the austere puritanism of Cromwell’s ten-year rule, Charles II was looked upon as a breath of fresh air; he was known as the Merry Monarch due to the atmosphere of hedonism at court. Invited to restore the monarchy in 1660, the three kingdoms of England, Scotland and Ireland began to return to the normality of the ancient regime. After the Commonwealth regime Charles was forgiven of much, such as his leanings both to Roman Catholicism and France. His marriage to Catherine of Braganza failed to produce an heir but his numerous affairs produced at least 12 children that he acknowledged, including a certain James Scott, born in Rotterdam during Charles’ exile.

Young James came to England at the age of 14 in 1663 and was awarded with the title of Duke of Monmouth. He became quite the dashing prince, earning a reputation as a competent military commander serving both abroad, in wars against the Netherlands and France, and at home, defeating a larger force of Scottish Covenanters at Bothwell Bridge in 1679, the irony of which would become clearer later. After such victories Monmouth grew ever more popular; crucially he was a Protestant but despite everything he achieved he was the illegitimate son of a king. As Charles II aged, the only legitimate heir to the three kingdoms was his brother the Catholic James. Amongst the Protestant establishment plots were hatched and a sense of paranoia gripped the kingdoms about the succession. Monmouth sought exile in the Dutch Republic after being implicated in the Rye House Plot which sought to kill both the king and his brother.

After a short illness Charles died in February 1685 and was succeeded by his brother James II of England and VII of Scotland. He soon faced two coordinated rebellions from Holland in opposing ends of the country that summer. Archibald Campbell, the earl of Argyll, landed in Scotland, while in predominately Protestant South West England Monmouth, in three ships, made land fall at Lyme Regis with 82 followers, four light field guns and 1500 muskets. The Duking Days had begun!

Taunton was planned to be his centre of operations but on arrival the town corporation, wealthier townsfolk and clergy opposed him. But among the clothworkers and the poor he found enthusiastic support and raised a regiment. Outside the White Hart Inn, local school girls presented him with a flag, and at sword point, the corporation members were forced to observe Monmouth being crowned king. Any celebration was short lived however, as in nearby Ashill Royalist forces defeated one of Monmouth’s patrols. The lack of guns and horses at his command was beginning to tell. Monmouth marched north with Bristol in his sights.

He moved through Bridgwater, gathering more men amid worsening weather. Meanwhile Royalist forces began to choke off support from neighbouring counties, tightening a noose around Somerset.

Mindful of Bristol’s southern defences Monmouth resolved to cross the Avon and attack from the East from Gloucestershire. Royalist cavalry harassed the rebels and stopped them forming up at Keynsham; in heavy rain the rebels turned back to Somerset. Without taking Bristol chances of success were becoming increasingly slim. Finding Bath fortified against them, Monmouth camped at nearby Norton St Philip. Royalist forces launched an attack but, much to their surprise, were quite effectively repulsed. There was no doubting their bravery, but however impressive as the rebels spirit was, it was clear that the Royalist forces were getting ever stronger and Monmouth’s ragtag forces could not hope to fight a conventional battle in the open against cannon and trained musket men.

Monmouth withdrew to Frome with the intent of heading into Wiltshire but found their path blocked by a now fully reinforced Royalist army. Morale began to collapse as news spread of the defeat of the Earl of Argyll. Emulating Alfred the Great, the rebels fell back to the Somerset Levels and found themselves hemmed in at Bridgwater.

Monmouth withdrew to Frome with the intent of heading into Wiltshire but found their path blocked by a now fully reinforced Royalist army. Morale began to collapse as news spread of the defeat of the Earl of Argyll. Emulating Alfred the Great, the rebels fell back to the Somerset Levels and found themselves hemmed in at Bridgwater.

Monmouth considered his options; without taking Bristol all hope for the rebellion would be lost. He fortified his position and sent men to Minehead where six cannon were known to be kept. From the church tower of St Mary's in Bridgwater, Monmouth saw the Royalist shadowing force of some 1,500 regulars and 500 cavalry camped at Westonzoyland on Sedgemoor. They had to be defeated to open the way east; a desperate plan took shape, which would be the last set piece battle to be fought on English soil.

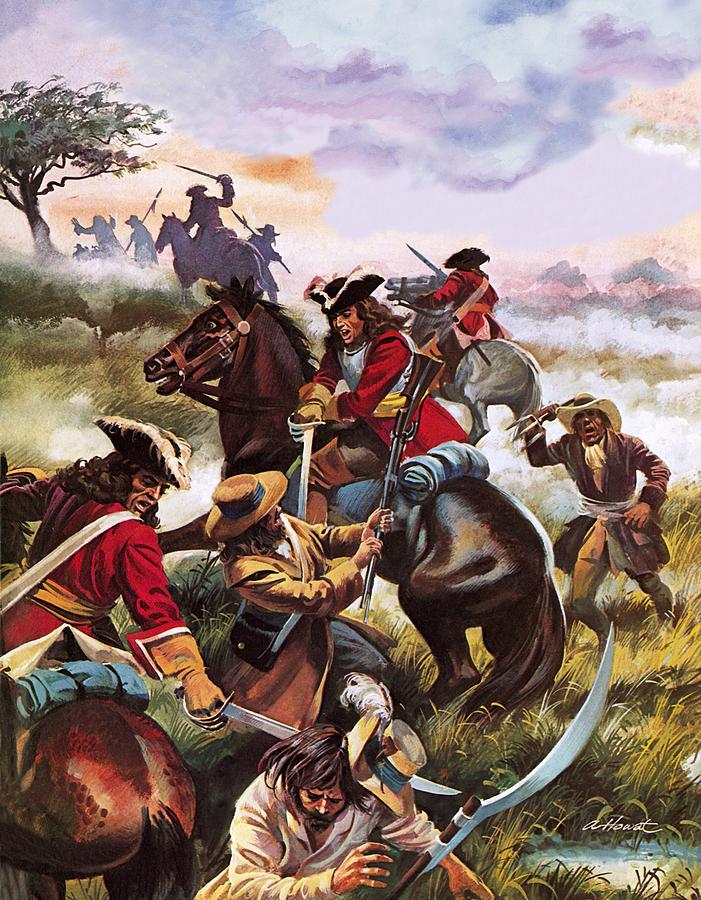

Monmouth’s army left Bridgwater and marched along Marsh Lane to the village of Bawdrip in the dead of night. To get to grips with the Royalist army they needed to navigate the network of deep drainage ditches (rhynes). Coming across a Royalist patrol a shot was fired and the Royalist army was called to arms. Gripping scythes and farm tools and shouting, “Come over and fight!” the rebels trapped behind a rhyne were exposed to volley after volley of muskets and cannon. There could be only one result; the rebels broke, to be hunted down mercilessly by the victorious troops, especially the Queen’s Regiment recently returned from Tangier, hanging suspects without trial.

Monmouth fled to Dorset but a price was on his head. He was soon captured and taken to London. It was said that he faced his end bravely, beheaded by multiple axe blows.

His supporters now faced the notorious Judge Jeffreys and his Bloody Assize. He cut a bloody swathe through the West Country and especially Somerset. Some 350 were hung while 800 were transported to the West Indies to work the plantations. His name became a curse and people questioned the cruelty of the hanging judge, although James rewarded him with the position of Lord Chancellor.

King James used the defeat of the rebellion as a chance to consolidate his power, bringing to reality the claims made against him by the rebels, even disbanding Parliament and threatening a return to the absolute monarchy that had sparked the Civil War a generation before. Only three years later, amid growing resentment, another invasion from Holland took place. The Glorious Revolution of 1688 led by William of Orange began in the West Country, readily gathering support among the people who looked on James with bitterness and hatred, recalling the Duking Days of 1685. Fittingly enough Judge Jeffreys himself was incarcerated and would die in in the Tower of London. It was said that he begged his captors for protection from a vengeful mob as he tried to follow King James, fleeing the approaching William III.

***

A couple of years ago driving across the Somerset Levels from a band practice I passed a sign indicating the battle site. As I drove on the lyrics of a song began to form...

We crowned our king in the Duking Days

and the county burst aflame.

We beat ploughshares into weapons.

And we swore to Monmouth's name.

We never lacked for courage.

But with pitchforks against guns.

On the bloody field of Sedgemoor

Our plans they came undone.

A Monmouth boys, a Monmouth

Monmouth is our man

A Monmouth boys, a Monmouth

Let’s win for him this land.

We crept along the Sedgemoor rhynes

On a moonlit summer's night.

To surprise the royal army

and bring them to a fight.

Was it just a horses neigh

or a musket's chance discharge?

Their cannon reaped a harvest.

As their camp was called to arms.

A Monmouth boys, a Monmouth

The man who would be king

A Monmouth boys, a Monmouth

We fight and die for him.

Our forces broke and scattered

The duke he fled the field.

Kingsmen swept the county.

Demanding all to yield.

The king sent for Judge Jeffreys

and by his bloody hand,

Eight hundreds sent to slavery.

Three hundred cruelly hanged.

A Monmouth boys, a Monmouth

That was our battle cry

A Monmouth boys, a Monmouth

Now the bloody assize.

As for our Duke of Monmouth,

three days he went to ground.

Cold and hungry in a ditch

their quarry was then found.

They dragged him back to London

to stand before the king.

He wept and begged for his own life.

Five axe blows finished him.

A Monmouth boys, a Monmouth

King James upon the throne

A Monmouth boys, a Monmouth

No mercy there was shown.

Oh we crowned him king in the Duking Days…

Rob Bayliss is a reviewer at The Review and is currently writing his own fantasy series. Information on his writing projects can be found at Flint & Steel, Fire & Shadow.

Rob, what a fabulous post. I found it thoroughly engrossing. I also think your lyrics are a good way to learn the history of this time.

ReplyDeleteExcellent post Rob. Will be sharing and tweeting. I am absolutely stunned by this post. I had no idea this guy had been crowned king even if it was never recognised. It has never been a time in history that has interested me that much but now I am so eager to learn more!

ReplyDelete