Forty

Years in a Day

By Mona Rodriguez and Dianne

Vigorito

Please see below for giveaway information of two copies of this fantastic novel

History is a fascinating

mirror and perhaps none is more so than the people who lived through it. Adding to

the layers of intrigue are oral traditions passed down within families that

lend new angles of perception and understanding to previous events, not least

of them being the awareness that these are one’s own people.

|

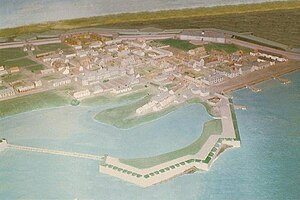

| Manhattan Island's Hell's Kitchen c. 1890, shortly before our story begins Photographed by Jacob Riis |

I’ve been fortunate recently

to have made the acquaintance of several books written about authors’ relatives

and ancestors, amongst them Forty Years in a Day, a family story told to one woman by her immigrant father on his 90th birthday. Having journeyed to Ellis Island, scene

of so many immigrant beginnings on our shores, the pair pass through the

interior of a building that “exploded with thousands of personal stories of

hardship and hope.” Clare sees her father’s face in those lining the walls,

these images reflecting the “disquietude of an era.”

She understands already that

the comfortable life she lives now is in debt to those who came before,

including her father, Vincenzo. His childhood journey from an Italian village to New York's Hell's Kitchen was marked with a near-death experience and instances of degradation his

mother, Victoria, tried to pass off as ordinary in the hope he would forget.

Whether Vincenzo recalls those earliest instances or retrieves them from his mother's diary is not articulated, but Rodriguez and

Vigorito lay out an understanding for Clare to absorb that is much larger than

any of it, suggesting that even had Vincenzo remembered, he is beyond it. As

father and daughter sit outside the island’s museum, silently taking in the

beauty of the crisp autumn afternoon, Clare remarks on the beauty of the day.

“My

father simply replied, ‘Clare, every day you’re alive is a beautiful day.’

Throughout

his life, the phrase ‘it’s a beautiful day’ had become his mantra. I had always

thought of it as cordial chitchat used to fill the uncomfortable gaps of

silence in conversations, but only now did I comprehend the depth of his

penetrating words.”

As they sit on the bench,

Vincenzo Montenaro tells his daughter Clare the story of his life and his

family, more precisely that of his mother, forced to leave an abusive husband

and board a ship alone with several small children. The language is

straightforward and accessible, but never simple, and the authors clearly work

well together, possessing a talent for relating details that elapse over a long

and arduous period of time, without overburdening the reader. We get a clear

sense of how awful is the journey and its inherent pains, terrors,

humiliations, discomforts, even cruelties.

This, in fact, is the style

of the entire novel—many years encapsulated in much the same way the elder

Montenaro would have done when taking only a single afternoon to describe forty

years of his life. It is part of the authors’ craft that one never really

knows for sure whether each individual segment is shortened by necessity or

because suggestion is more powerful than a full-on witnessed account. Indeed,

certain details are too wrenching to lay openly on the table, so to speak, and

in fact would not do them justice. Some things, as is oft repeated, are best

left to the imagination.

Vincenzo takes Clare—and

us—through his mother’s story, her journey with the children to America and the

years in which her life is essentially on hold because she mistakenly believes

the husband she fled lives on. As time moves forward, Victoria, and her family as well as

society, experiences growth and the awkward, inspirational and even ordinary

moments informing and directing decisions pertaining to children, careers,

dating, friendships, recreational activities, marriage and children, crises,

illness and death, war, struggle, failures and triumph, and looking towards the

future while remembering dreams of the past.

|

| Mission House in Hell's Kitchen c. 1915 |

Somehow the myth pertaining

to this era’s more “innocent” time has managed to stay afloat in our own society, though Rodriguez

and Vigorito attempt no such fluff. Life at this time was difficult, even

nightmarish for some, though there were opportunities as well. New York City in

the first half of the 20th century was no playground: Irish mafia

wars rivaled disease and poverty and though many emerged intact, very few

escaped at least some contact with both.

But, like life in any era,

there existed also the beauty of the ordinary, perhaps what Vincenzo, even in

childhood, reveled in the most as he passionately embraced his appreciation for

life:

Victoria

knew the smell of the fresh baked bread and sauce simmering on the stove were

ones the children looked forward to six days to Sunday. The minute she and

[sister-in-law] Genevieve left the kitchen to ready themselves for church,

Vincenzo would rip a loaf of the warm bread into pieces, dunk them into the

sauce, and dole them out to his cousins and siblings. By the time Victoria

returned, washcloth in hand, one of the loaves would have inconspicuously disappeared.

Smiling to herself, she would casually wipe away the residue of red that rimmed

their lips, pretending she was unaware of their weekly ritual.

Perhaps one of the novel’s

greatest strengths is the manner in which it balances understanding of one realism

within history: from the beginning human beings have always loved to be told

stories, and it is no accident that our own histories resonate so deeply within us. The series of stories told throughout the book, as Vincenzo and his

siblings—and the enlarging cast of characters—journey though teen years and

young adulthood, as they enter into middle age, these stories satisfy a need to

know about life for others and at other times, told by two with the eye and instinct of

keen storytellers who know exactly when to divulge, when to pause and hold onto

secrets and twists. They also embody the mirror image of those who love to be

told a tale by fully displaying the seeming human satisfaction in telling one. Effortlessly

weaving through time and connections within the characters’ own era,

neighborhood and circles, they also touch our own.

So much happens in this novel, really a memoir of sorts--beginning in first person and shifting away as Vincenzo picks up--but readers are moved forward, perhaps a reflection of Vincenzo's own perspective and the manner in which he habitually looks forward, rarely dwelling on past events Here, too, the authors, who are in fact cousins telling their own family's story, bring us to witness exactly how much the patriarch values the future and those who will occupy it. Like Clare who learns so much that afternoon, readers will be "exhausted and inspired from the journey[,]" and wouldn't have it any other way.

So much happens in this novel, really a memoir of sorts--beginning in first person and shifting away as Vincenzo picks up--but readers are moved forward, perhaps a reflection of Vincenzo's own perspective and the manner in which he habitually looks forward, rarely dwelling on past events Here, too, the authors, who are in fact cousins telling their own family's story, bring us to witness exactly how much the patriarch values the future and those who will occupy it. Like Clare who learns so much that afternoon, readers will be "exhausted and inspired from the journey[,]" and wouldn't have it any other way.

Mona Rodriguez and Dianne Vigorito have so graciously offered two copies of Forty Years in a Day for giveaway. To become eligible, simply comment below or at this review's associated Facebook thread.

You can learn more about the authors and Forty Years in a Day at their website or blog, or follow on Twitter or Pinterest. You may also find Forty Years in a Day for purchase at Amazon.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)