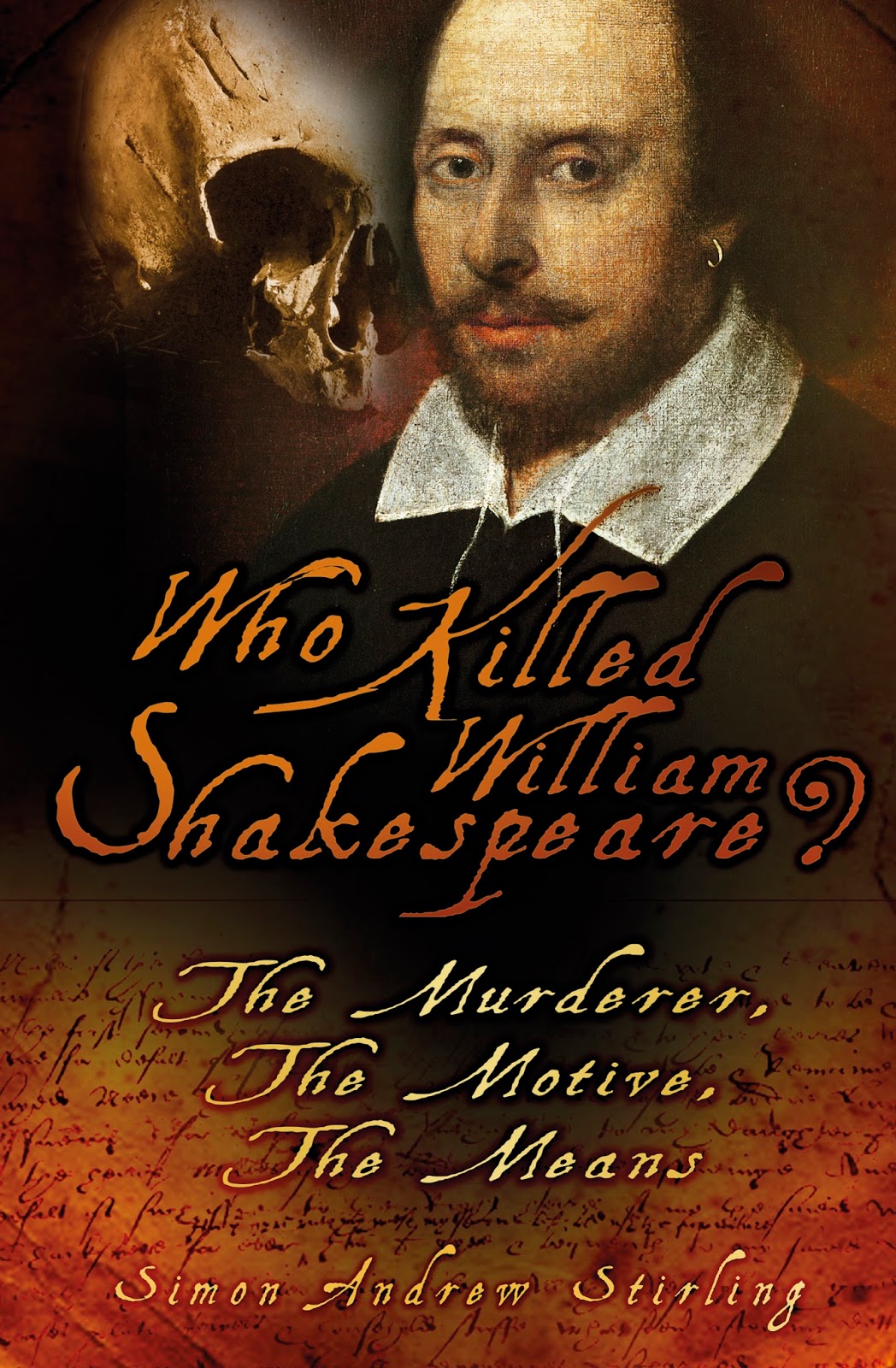

Thanks to Simon for coming along and being a guest on Paula's People. Simon discusses the ideas that spawned his latest novel Who Killed William Shakespeare?

I was chatting to (chatting up?) a Canadian student at my drama school in London, one day.

“So – got anything planned for this weekend?”

“Yeah, we’re all going up to Stratford-upon-Avon. We’re seeing a show at the Royal Shakespeare Theatre, and we get the Shakespeare tour.”

It was part of the one-year course for overseas students: the Stratford Weekend. And that’s when it struck me. To lovers of theatre, and literature, all over the world, Stratford is a kind of Mecca.

And there was me thinking it was a place you went to on a Sunday afternoon.

I’ve spent a great deal of my life in and around Shakespeare’s hometown. It’s given me a different perspective on the ‘Sweet swan of Avon’. Time after time, reading biographies of William Shakespeare, I was struck by how little interest the biographer had in Shakespeare’s native region, his family connections, the knotty network of friends and co-religionists which made Warwickshire such a tribal county.

London has changed since Shakespeare’s day. But much of his home county hasn’t altered that much. You can get closer to Shakespeare in the lanes around Baddesley Clinton or Earls Common than you ever can on the banks of the Thames.

When I started studying Shakespeare in the late-1980s, hoping to understand how a lad from the Midlands became the world’s greatest poet-playwright, I found it all a frustrating experience. “We know so little about him!” seemed to be the cry on every Shakespeare scholar’s lips. Twenty-five years on, I’ve come to believe that this mantra is anything but true. By refusing to concentrate on his London days, I was able to uncover several new facts about Shakespeare’s life. A whole new picture emerged – more ‘real’, if you will, and certainly more intriguing. Downright scary, at times.

But the mythology of Shakespeare forms most of what we know, or think we know, or are told to think we know, about this brilliant man. To engage properly with Shakespeare is to enter the terrifying world of Tudor and Jacobean politics, something unnervingly close to a police state, and the sheer brutality of the repression of those who adhered to the Catholic faith, as their forefathers had done for a thousand years. It is to enter a period of great upheaval, a massive redistribution of wealth, the remorseless rise of a new political class and a casual recourse to murderous violence. It was a time of fear and favour, of propaganda and prejudice.

At least, it is if you study it. If you just read up on Shakespeare, though, you’ll come across very little of this. Rather, you’ll be treated to a picture-postcard image of Merrie England, with Good Queen Bess on the throne and men prancing about in tights. What was happening in the background, and often on a public scaffold, is seldom mentioned.

I lost track of the number of Shakespeare’s associates – his friends and relatives and contacts – who died in the most horrific ways possible (this presented me with a writer’s problem: how do you convey the reality of hanging, drawing and quartering – the state’s standard punishment for treason – and how do you keep that reality fresh and meaningful after the twentieth execution?). For years, Shakespeare scholars have insisted on approaching his plays and poems as if they just popped out of his head, appearing from nowhere, each little nugget a witness to his rare genius but nothing whatever to do with his thoughts about what was going on at the time.

Would Shakespeare have been Shakespeare if he had turned a blind eye to the crimes that were being committed, all around him, by paranoid, vengeful, greedy and self-serving ministers? Could he have been a poet and yet somehow avoided a little spying on the side? Few of his contemporaries did, and yet Shakespeare is usually treated differently from his colleagues. It’s as if we don’t want to admit that he was a real person … or we don’t want to have to deal with the realities of his life.

And so, many a promising lead is ignored, many an intriguing rumour stifled, so as not to tarnish our falsified ideas of the Bard. Evidence has indeed vanished, and many a line of inquiry has gone cold through lack of academic curiosity. One such line was the story published by a Warwickshire clergyman in the 1880s.

The vicar first claimed – in a remarkably detailed account – that Shakespeare’s skull had been stolen from Stratford. He added to that account five years later, when he described his discovery of Shakespeare’s skull in another church altogether. The tale of ‘How Shakespeare’s Skull Was Stolen and Found’ has received little or no attention from the Shakespeare experts. Which is a pity, because much of it turns out to be true. Most remarkable of all, there is a spare skull in the very crypt described by the Warwickshire vicar, and it bears comparison with the portraits of William Shakespeare.

Maybe the story was ignored because the skull was found in what can only be described as the most Catholic resting place in the whole of the English Midlands. Or maybe – just maybe – too many Shakespeare scholars aren’t really interested in him at all. They are simply promoting a rose-tinted view of England’s past.

The real William Shakespeare has no place in that quaint and cosy misrepresentation of history. So they continue to sell a Shakespeare who never was.

But if we want to understand him, and to hear his words clearly, and to know what atrocities were committed in the names of Queen Elizabeth and King James, we have to look at all the evidence. Skulls and all. It makes for a richer tapestry, if a bloodier one, and his plays seem all the fresher for it.

Just as long as we don’t fall into the trap of thinking of Stratford-upon-Avon as a kind of Mecca. Shakespeare and his kind don’t demand our worship.

They demand justice. And it’s long overdue.

Andrew Stirling is the author of The King Arthur Conspiracy: How a Scottish Prince Became a Mythical Hero (2012) and Who Killed William Shakespeare? The Murderer, the Motive, the Means (2013) – both published by The History Press and available in Kindle editions from Amazon and in hardback from a variety of outlets. His latest project, The Grail; Relic of an Ancient Religion, will be published by Moon Books later this year.

I was chatting to (chatting up?) a Canadian student at my drama school in London, one day.

“So – got anything planned for this weekend?”

“Yeah, we’re all going up to Stratford-upon-Avon. We’re seeing a show at the Royal Shakespeare Theatre, and we get the Shakespeare tour.”

It was part of the one-year course for overseas students: the Stratford Weekend. And that’s when it struck me. To lovers of theatre, and literature, all over the world, Stratford is a kind of Mecca.

And there was me thinking it was a place you went to on a Sunday afternoon.

I’ve spent a great deal of my life in and around Shakespeare’s hometown. It’s given me a different perspective on the ‘Sweet swan of Avon’. Time after time, reading biographies of William Shakespeare, I was struck by how little interest the biographer had in Shakespeare’s native region, his family connections, the knotty network of friends and co-religionists which made Warwickshire such a tribal county.

London has changed since Shakespeare’s day. But much of his home county hasn’t altered that much. You can get closer to Shakespeare in the lanes around Baddesley Clinton or Earls Common than you ever can on the banks of the Thames.

When I started studying Shakespeare in the late-1980s, hoping to understand how a lad from the Midlands became the world’s greatest poet-playwright, I found it all a frustrating experience. “We know so little about him!” seemed to be the cry on every Shakespeare scholar’s lips. Twenty-five years on, I’ve come to believe that this mantra is anything but true. By refusing to concentrate on his London days, I was able to uncover several new facts about Shakespeare’s life. A whole new picture emerged – more ‘real’, if you will, and certainly more intriguing. Downright scary, at times.

But the mythology of Shakespeare forms most of what we know, or think we know, or are told to think we know, about this brilliant man. To engage properly with Shakespeare is to enter the terrifying world of Tudor and Jacobean politics, something unnervingly close to a police state, and the sheer brutality of the repression of those who adhered to the Catholic faith, as their forefathers had done for a thousand years. It is to enter a period of great upheaval, a massive redistribution of wealth, the remorseless rise of a new political class and a casual recourse to murderous violence. It was a time of fear and favour, of propaganda and prejudice.

|

| 16thc priest |

I lost track of the number of Shakespeare’s associates – his friends and relatives and contacts – who died in the most horrific ways possible (this presented me with a writer’s problem: how do you convey the reality of hanging, drawing and quartering – the state’s standard punishment for treason – and how do you keep that reality fresh and meaningful after the twentieth execution?). For years, Shakespeare scholars have insisted on approaching his plays and poems as if they just popped out of his head, appearing from nowhere, each little nugget a witness to his rare genius but nothing whatever to do with his thoughts about what was going on at the time.

|

| Romeo and Juliet |

And so, many a promising lead is ignored, many an intriguing rumour stifled, so as not to tarnish our falsified ideas of the Bard. Evidence has indeed vanished, and many a line of inquiry has gone cold through lack of academic curiosity. One such line was the story published by a Warwickshire clergyman in the 1880s.

The vicar first claimed – in a remarkably detailed account – that Shakespeare’s skull had been stolen from Stratford. He added to that account five years later, when he described his discovery of Shakespeare’s skull in another church altogether. The tale of ‘How Shakespeare’s Skull Was Stolen and Found’ has received little or no attention from the Shakespeare experts. Which is a pity, because much of it turns out to be true. Most remarkable of all, there is a spare skull in the very crypt described by the Warwickshire vicar, and it bears comparison with the portraits of William Shakespeare.

|

| St Leonard's church in Beoley where Shakespeare's skull was found |

The real William Shakespeare has no place in that quaint and cosy misrepresentation of history. So they continue to sell a Shakespeare who never was.

But if we want to understand him, and to hear his words clearly, and to know what atrocities were committed in the names of Queen Elizabeth and King James, we have to look at all the evidence. Skulls and all. It makes for a richer tapestry, if a bloodier one, and his plays seem all the fresher for it.

|

| The Skull believed to be Shakespeare's |

They demand justice. And it’s long overdue.

Andrew Stirling is the author of The King Arthur Conspiracy: How a Scottish Prince Became a Mythical Hero (2012) and Who Killed William Shakespeare? The Murderer, the Motive, the Means (2013) – both published by The History Press and available in Kindle editions from Amazon and in hardback from a variety of outlets. His latest project, The Grail; Relic of an Ancient Religion, will be published by Moon Books later this year.

Simon lives in Worcestershire, UK, and lectures in Film Studies and Screenwriting at the University of Worcester. He is also a respected member of The Review. Follow his blog at www.artandwill.blogspot.co.uk.

Facebook readers may also comment here.

What a wonderful article, one that touches the heart of all my knowledge (or lack thereof) about Shakespeare. Absolutely brilliant, Simon.

ReplyDeleteGreat article. Really enjoyed reading it

ReplyDeleteFantastic post. Enjoyed it and I am very intrigued now about the real William Shakespeare.

ReplyDeleteI loved reading this article. I am the proud owner of both of Simon's books and would recommend them most highly.

ReplyDeleteWay to whet our appetite and make us want to read the book, Who Killed William Shakespeare which, I presume, answers many of the fascinating questions raised here. I would only argue that there ARE people who are looking at the real events that took place during that horrible time that Simon describes, and they are historians, fiction writers and playwrights. The play EQUIVOCATION by Bill Cain, for example, deals with an artist (Shakespeare) struggling to balance loyalty to his country with his personal sense of justice and morality. It is a riveting play. Judging from this intriguing essay, I expect that Simon's book is riveting, too. I look forward to reading it.

ReplyDeleteI once visited Shakespeare's hometown and as Simon said, it brought me closer to the real person. I'm generally tired of the Tudors, but must say this article has intrigued me. I'd be willing to read this with an enthusiasm I thought lost. Thanks very much for the lovely discussion.

ReplyDelete